As a shareholder of Swire Properties, I can live with the HK$475 million apartment in Frank Gehry’s Opus project. Whoever bought it is now the proud owner of a supposed (rather disheveled-looking, to me) architectural trophy. As a transaction, the sale has no connection with the real Hong Kong housing market. The problem is that much of the other residential real estate in town seems to have become similarly disconnected: the city needs affordable dwellings for people and families, but interest rates, government and developers have turned housing stock into overpriced assets – stores of value for investors, if not quick punts for speculators betting on more ‘store of value’ fans joining the rush.

As a shareholder of Swire Properties, I can live with the HK$475 million apartment in Frank Gehry’s Opus project. Whoever bought it is now the proud owner of a supposed (rather disheveled-looking, to me) architectural trophy. As a transaction, the sale has no connection with the real Hong Kong housing market. The problem is that much of the other residential real estate in town seems to have become similarly disconnected: the city needs affordable dwellings for people and families, but interest rates, government and developers have turned housing stock into overpriced assets – stores of value for investors, if not quick punts for speculators betting on more ‘store of value’ fans joining the rush.

Recent land auction results and transactions in middle-class neighbourhoods suggest continued price rises. The property bulls scoff at the question of whether to buy or bail. They point to continued global monetary loosening, which debases the dollar and other currencies, which drives people to convert cash into real assets that will keep their value. Thus more quantitative easing or negative real interest rates must mean yet more upside for the Hong Kong property market. (The rest of the world has gold bugs.)

However, so far as we can see, the ongoing debasement of the currency is counteracting what would otherwise be a severe rebasing through debt-deflation and 1930s-style recession. This must be part of the reason why we are not seeing inflation soar (so far as we can distinguish ‘monetary’ price changes from ‘supply-and-demand’ ones). No-one’s pushing cash around in wheelbarrows to buy groceries. Hong Kong property prices are galloping far ahead not only of inflation, but of most other assets that can protect people from debased currencies.

There may be unique or unusual political, cultural or psychological factors at play. Maybe it is safer or easier to launder dirty Mainland money via Hong Kong property than any other way, so the launderers happily pay double what the asset is worth so the worst-case scenario is that they keep 50% of their illicit millions. Maybe well-off Hongkongers are so sheep-like that local property is their entire investment universe. But even so, how sustainable is it? How long can one asset class in one city outperform so many other assets and locations?

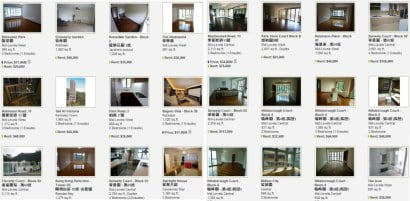

Property bulls like to point out that this time, at least, the Hong Kong property market isn’t over-leveraged as in 1997, when secretaries were buying multiple units with 100% mortgages. But that doesn’t necessarily mean current (or next month’s even higher) prices make sense. How much future debasement of currency has already been priced into middle-class Hong Kong property? What happens if less debasement than anticipated takes place? How long can the nominal prices maintain their distance from the real economic value of these concrete boxes? Or, if the debasement does materialize, what happens to other real asset prices that have so far lagged (and what impact does that have on Hong Kong property)?

It wouldn’t matter if the only thing at risk was a herd of relatively wealthy people with a laid-back attitude to having lots of eggs in just a few baskets. The danger lies in the political unsustainability of these price rises. How many monthly declines in housing affordability will young people put up with before they get angry? How long before, say, a mob of 20-something ‘snails without shells’ burst into a luxury showflat and trash the place in front of terrified Mandarin-speaking apartment buyers? The amazing thing about a recent straw poll on the issue is that 10% of respondents didn’t think housing was too expensive.

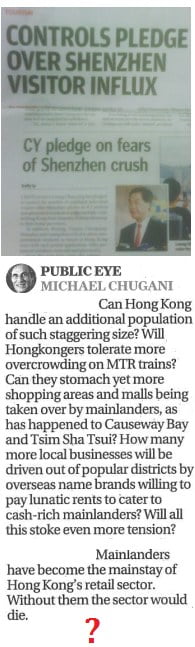

Chief Executive CY Leung came into office promising to fix the problem. If he hoped his mere presence would cool the market, he has been proved wrong. Like his predecessors towards the end, he is petrified both of prices going up and coming down. On Planet Earth, cheaper housing is good because it means families have more money left over to buy education, food, shoes, health care, cars, books, plasma TVs, scuba-diving vacations, ice cream, kitty litter, and a million other things. In Hong Kong,  the prospect is sinister and fearful; we would rather talk about cancer.

the prospect is sinister and fearful; we would rather talk about cancer.

Also like his predecessors, CY has an almost-irrational fear – almost a superstition – about cooling the market with words. All he has to tell the public, on prime-time TV, is: “If you want a home, don’t buy at these prices – they’re out of alignment with any sane measurement of the true worth of a concrete box. Just wait.” The last official to do that was then-Financial Secretary Donald Tsang in early 1997. When prices carried on rising for a few months, the secretaries and taxi drivers whined bitterly that he had made them miss their chance. How grateful they must have been a year later.

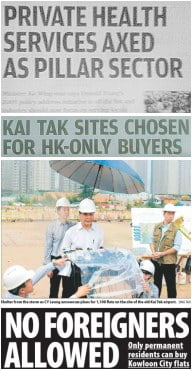

So – voila: CY’s first stab at solving what will end up as a political crisis at some stage. It’s more PR than anything else, but three things stand out.

First is the reliance on ad-hoc ring-fenced schemes like HOS, MHPP and URA. This is like demarcating little zones on a map in which small numbers of apartments will be effectively tax-free for some lucky winners; the rest of the market remains ‘healthy’ – that is prices can rise or stay stable, but never come down, no, no, no.

Second is the rezoning and other planning jiggery-pokery to convert or redevelop industrial and other non-residential sites for housing. A six-year-old would consider it, but there is a huge bureaucratic hang-up about this sort of thing, based on the colonial assumption that the government’s main job is to extort wealth from the population via land sales. Just minor liberalization is a good precedent.

Third is the ‘Hong Kong land for Hong Kong people’ idea – or lack of it. Some purists oppose the concept by bleating about free markets (where all the land is nationalized?) or even a slippery slope leading to capital controls. A more pressing problem would be the danger of appearing to indulge populist anti-locust feeling at a time like this, and increasing anti-Hong Kong sentiment on the other side of the border. There are also supposed to be implementation and legal issues, too, though other jurisdictions manage it OK.

Long term, CY is no doubt serious about designing a proper system for planning and providing sufficient housing for Hong Kong. After the lurching and panicking and ratcheting-up of property prices under former CE Donald Tsang, anything will look like good governance. But in the nearer term, the policy remains the same: make some gestures and keep your head down for when the market suddenly decides of its own volition to stop being so ‘healthy’.

Click to hear Roxy Music’s ‘In Every Dream Home a Heartache’!

Sir Bow-Tie’s obsession with making health care a ‘pillar industry’. Hospitals will now be for Hong Kong people – a constituency the last administration saw as a nuisance.

Sir Bow-Tie’s obsession with making health care a ‘pillar industry’. Hospitals will now be for Hong Kong people – a constituency the last administration saw as a nuisance.