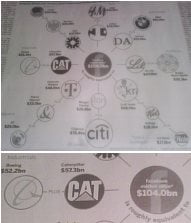

What are things worth? Saturday’s Financial Times had a diagram bundling comparable companies together so their combined stock market capitalization equaled that of just-launched Facebook’s US$100 billion. Thus the biggest telecoms operator in each of Germany, France and the UK total Facebook in value, as do three big UK banks and each of the pairs Eli Lilly-Bristol Myers Squib and Boeing-Caterpillar.

What are things worth? Saturday’s Financial Times had a diagram bundling comparable companies together so their combined stock market capitalization equaled that of just-launched Facebook’s US$100 billion. Thus the biggest telecoms operator in each of Germany, France and the UK total Facebook in value, as do three big UK banks and each of the pairs Eli Lilly-Bristol Myers Squib and Boeing-Caterpillar.

Maybe banks are unpopular and pharmaceuticals companies controversial, but most of us would say that Boeing and Caterpillar make products that have made the world a better place. The idea that something as idiotic as Facebook has the same market value as both equipment manufacturers put together is almost ludicrous. Yet people were paying US$45 for Facebook on Friday, before it ended up at $34 yesterday.

(It probably doesn’t help that I still can’t work out what Facebook is for, or find a reason to obey the emails begging me to visit my own virtually abandoned Facebook page. Recently, I’ve noticed that unrelated websites have started featuring little Facebook panels saying someone I know enjoyed this or that feature, which is annoying, if not almost creepy – as if Mark Zuckerberg’s people are following me around.)

Glorious Tuen Mun has its own version of Facebook: Century Gateway, a Sun Hung Kai Properties residential development. All yours (as of a couple of weeks ago) for HK$13,000 a square foot. Obviously, no-one in their right mind is going to pay that much for a home in one of the less desirable parts of Western New Territories; if you need to live there – someone might – you buy a place for half that, or rent. So the idea here is to lure in suckers who think there is more upside, that more quantitative easing is going to debase the currency, and that people with impoverished imaginations will continue to pour into Hong Kong property regardless of how out of step prices become with other asset classes, from gold to art to farmland to Facebook shares. They might be right; then again, they might be overlooking something, like the deflationary impact of trillions of global debt. But what is an apartment in Tuen Mun worth? What is the value of its economic benefits to humanity, as a badly located and no doubt poorly designed shelter?

Glorious Tuen Mun has its own version of Facebook: Century Gateway, a Sun Hung Kai Properties residential development. All yours (as of a couple of weeks ago) for HK$13,000 a square foot. Obviously, no-one in their right mind is going to pay that much for a home in one of the less desirable parts of Western New Territories; if you need to live there – someone might – you buy a place for half that, or rent. So the idea here is to lure in suckers who think there is more upside, that more quantitative easing is going to debase the currency, and that people with impoverished imaginations will continue to pour into Hong Kong property regardless of how out of step prices become with other asset classes, from gold to art to farmland to Facebook shares. They might be right; then again, they might be overlooking something, like the deflationary impact of trillions of global debt. But what is an apartment in Tuen Mun worth? What is the value of its economic benefits to humanity, as a badly located and no doubt poorly designed shelter?

We could ask the same about an outdated Scandinavian system for heating homes and cooking food. How much will the Chinese pay for a kitchen range that is always on, and thus uses more energy in a week than a standard oven does in nine months – namely the Aga?

Apparently, the manufacturers are working on models that can be switched off. I can imagine their CEO, William McGrath, slapping the side of his head and saying, “Duh, I wish we’d thought of that before.” I can imagine it because he has plans to sell the huge contraptions in the Mainland and has said: “In China, most standard kitchens just have two big burners in them … That’s a long way away from a western-oriented kitchen, but I think that could be radically changed in the next few years.”

Apparently, the manufacturers are working on models that can be switched off. I can imagine their CEO, William McGrath, slapping the side of his head and saying, “Duh, I wish we’d thought of that before.” I can imagine it because he has plans to sell the huge contraptions in the Mainland and has said: “In China, most standard kitchens just have two big burners in them … That’s a long way away from a western-oriented kitchen, but I think that could be radically changed in the next few years.”

If there were an Ethno-centric Western Businessman of the Year Award, he would win. He thinks Chinese kitchens will triple or quadruple in size in the next few years, while a billion people will throw their woks away and will never stir-fry anything again and start eating only stodgy stewed and baked gwailo food with gravy all over everything. The only possible way to sell Agas in China would be to stress how overpriced, wasteful and pointless they are, so people might brag about having one; the Aga company survives because it managed to position its product as a status symbol among the nouveau-riche in the UK. This brings us to the alternative universe where microeconomic laws of demand yield to psychology, if not biology.

In reality, Agas have no (non-scrap) value to the Chinese because, as this ad man points out, Mainlanders pay a premium for things they consume in public but penny-pinch on household appliances and things others don’t see. Status symbols boost their owners’ sense of self-worth – and try putting a dollar valuation on  that. The rest of us will see them carrying a pricy item, the theory goes, and we will, to cut a long story short, want to mate and breed with them so their clearly superior DNA will give our rather humdrum self-replicating proteins a free ride to continued existence.

that. The rest of us will see them carrying a pricy item, the theory goes, and we will, to cut a long story short, want to mate and breed with them so their clearly superior DNA will give our rather humdrum self-replicating proteins a free ride to continued existence.

In practice, a highly visible status symbol might impel a prospective mate to run away screaming in terror, clutching his credit cards. Like this thing in the window of Italy Station, the second-hand handbag store. The unique nastiness of the colour scheme, partly day-glow chartreuse, partly puce, grabbed my attention at first. Then I saw the price tag: HK$268,000 – and that’s fixed, so don’t bother haggling. I thought it was a joke or a mistake, but Hong Kong retailers don’t do either. Maybe the colours are misleading, and the item reflects an ancient tradition of exquisite Italian workmanship, but even so: what are you getting for the other 267 grand?

Let’s be charitable: it’s 1,000 shares in Facebook; it’s around a couple of Agas (including what they call ‘commissioning’); it’s probably just about the down-payment for a little second-hand apartment in Tuen Mun. Seen that way, it’s a bargain.

![]() So along I go to Li Yuen Street West, one of the little alleyways full of stalls selling ultra-cheap touristy tat like kids’ kimonos and plastic watches. And there the store is: I must have passed it dozens of times, yet it had never registered, despite having an open front and the distinctive logo above it.

So along I go to Li Yuen Street West, one of the little alleyways full of stalls selling ultra-cheap touristy tat like kids’ kimonos and plastic watches. And there the store is: I must have passed it dozens of times, yet it had never registered, despite having an open front and the distinctive logo above it.