You’ve heard all about the famines, the lack of fuel, the labour camps, the social regimentation and other horrors. You’ve read about the starving roaming the country, the bodies in the streets and the illicit cross-border traffic with China. You might know about the intellectuals sent off to the hills to find food, the workers scavenging equipment and machinery (for food), the women marrying Mainland farmers (for food), and even rumours of cannibalism. Now, meet the North Korean people themselves in Nothing to Envy by Barbara Demick.

The place is the far-northern city of Chongjin. The story starts in the early 1990s, around the time Kim Il-sung died and gave way to his son Kim Jong-il and economic collapse. Welcome to the world of: Mi-ran, the demure teacher of officially suspect ancestry who sees her young class fade away; Jun-sang, the high-flying student with whom she has a secret, decade-long, relationship; Mrs Song, the devoutly pro-regime housewife; Oak-hee, her rebellious daughter; Kim Hyuck the stunted, street-urchin survivor; and Dr Kim, the idealistic physician whose hospital patients have to bring their own beer bottles for IV drips.

Their world, long deteriorating, falls apart. Salaries dry up, electricity fails, food rations dwindle to nothing, relationships and families disintegrate. By the late 1990s, over 10% of North Koreans have perished, and a whole generation of kids are permanently damaged. The decent and law-abiding die first. In order to get through it alive, the author writes, “one had to suppress any impulse to share food.” The athletic and tall, needing more calories to function, go next.

This oral history based on interviews with defectors in the South during the 2000s is a work of heart-tugging journalism. The author herself concedes that she has no way of verifying the accounts, though attempts to cross-reference and fact-check suggest they are accurate. People pick through animal droppings for kernels of corn; workers with carts do a daily round at the train station for corpses; those with the presence of mind, resources and (rare) opportunity, try to get out.

The ethnic-Korean region across the border in China is the only hope. By the 2000s, enough desperate and hungry people have done it that a risky but lucrative business exists in trading plundered scrap or smuggling people to the other side. One by one, our six anti-heroes find themselves wading across the frozen Tumen River in the pitch dark with no idea what awaits them. For Dr Kim, the first revelation is that everything she has been told about the supremacy of her homeland is a lie: she swings open the gate to someone’s courtyard, sees – for the first time in years –a dish of white rice and meat before her, and then realizes it is for a dog.

Eventually, after various adventures, we see them emerging from a debriefing and resettlement centre near Seoul with a cash handout and lessons in how to use an ATM and read the Roman alphabet. Do they live happily ever after in prosperous, free, democratic South Korea? It seems not.

Oak-hee, for example, gets by as a mama-san in an industrial town, running (Northern) bargirls. Jun-sang finally catches up with his sweetheart Mi-ran – who, like everyone, left without a word – to find she is already married and has a baby. These refugees suffer terrible guilt. Flight is an act of desperate selfishness: you not only abandon children, spouses and parents, you condemn them to prison camp or worse. The author writes of Mi-ran: “Her sisters had paid the ultimate price so she could drive a Hyundai.” Kim Hyuck, on the other hand, has nowhere to go but up, and widow Mrs Song gets into leather pants and has her eyelids done. But Northern qualifications are useless and prospects are limited.

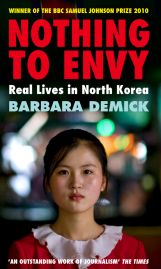

An epilogue brings us up to the sinking of the Cheonan last March and the latest reports from a decayed Chongjin. When they fled, the six characters mostly assumed the regime was approaching final collapse, and they would soon be able to return, maybe get relatives out of detention and help rebuild their country. Now they are stuck in the South. Demick has been careful not to overdo the emotion and keep the narrative gripping yet worthy of the LA Times, where the book has its origins. But, as the Granta edition’s cover hints, this could be a real tear-jerker of a movie.

“Her sisters had paid the ultimate price so she could drive a Hyundai.”

Smacks of sensationalist journalism to me.

Life Expectancy North Korea: 67.15634 years.

Life Expectancy for Black males in the USA: 69.2 years.

11% of all Black men in the USA aged 20-34 are in prison.

Blacks are 13% of the population but 50% of the prison population.

There are two million US citizens in jail, the largest population of prisoners on earth.

In 2009, 1 in 31 Americans was in jail, on parole or on probation.

The triumph of capitalism!

Historian: Not at all. Read the book! It’s excellent.

One day Historian we won’t need to write shock horror books about other countries.

We will just have real journalists at home!

Deadrat: life expectancy North Korea: 67.15 years

That number only applies to Politburo members (the only people who count, and are being counted, in the people’s paradise of North Korea).

“11% of all Black men in the USA aged 20-34 are in prison.”

As compared to 100% of everyone in North Korea, bar the minute number at the the top of the regime.

The average US prison food regimen would probably equate to the combined diet of 4-5 North Koreans in caloric yield.